A Canvas for the Assumptions of Others

A Canvas for the Assumptions of Others

by Lisa Rosenberg

(Printed by the permission. This essay wasoriginally published here: http://lisawrosenberg.com/

You are the “other” box. Maybe not quite black, yet clearly not white. Or not visibly black, but something off-white. You are “exotic.” Possibly Armenian? Koori? Dominican? Really, really tan? No, you’re biracial, mixed, mulatto, colored, depending where in the world you hail from. You’re Both/And.

For some of us, the Barack Obama’s the Halle Berry’s and me, black is a convenient short-hand for our identity. It is how we appear to strangers, and doesn’t cause a stir or elicit extra questions. Black is also a way of adding our numbers to a much-maligned minority. But black skips out on half our story, half of our parentage and identity.

For the Jennifer Bealses, the Rashida Joneses, the black piece of the package is what people question. In both situations, there is a parent whose ancestry is less visible than the other.

And then there are those in the middle, the racially-ambiguous looking, where the trained eye can see a little of everything. In this spot, you’ll be facing the “what are you?” question more than the others, who tend to quickly be (if incorrectly) categorized by strangers. In the middle, you throw people off.

Now I’m wading into the deep waters of “Ascribed Identity,” a concept I first read about in graduate school when Dr. Elaine Pinderhughes came to present on her book, Understanding Race, Identity and Power. Ascribed identity has little to do with who you actually are and everything to do with how others see you—their snap-judgments, the stories they tell themselves about who and what you are—based on your appearance alone. No matter how far from the truth these inferences are, you deal with them all day long—in the questions people ask, the treatment you receive. Other people’s stories and judgments—whether you believe them or not, whether you know about them or not—are part of your identity. Even when they are totally false. It’s that flicker of here-we-go-again awareness anytime someone compliments your diction or asks where you are “from.”

When you are mixed, this ascribed stuff can feel like a costume that doesn’t quite fit, but that’s always going to be somewhere in your closet nevertheless. It’s important to be aware of it, to be prepared for the things people say and assume. But the good news is that our ascribed identities need have no bearing on our self-concepts, our behavior or choices. For example, I have been judged for not speaking “black,” for not wearing my hair in braids, even for being the wrong weight for my color. (That really happened).

Sometimes, being biracial can feel like being a canvas for other people’s creative assumptions.

My favorite section of Dr. Maria Root’s Bill of Rights for People of Mixed Heritage (that I think I quoted three or four posts ago) is this one: “I have the right to self-identify. To identify myself differently than strangers expect me to identify.”

Frankly, I think this right applies to everyone—not just those of mixed heritage. But when it comes to us biracial types, there are a great many opinions on how we should identify ourselves racially, ethnically and otherwise.

After hearing Pinderhughes speak, my fellow social work students and I were suddenly thinking about identity more than we ever had before. Our daily vocabulary included not just ascribed identity, but also terms like use-of-self and cross-cultural competence. Like everyone else, I was grappling with what it meant to be me—how I was perceived versus who I was and how my background affected my work with clients. When I identified as biracial, black and Jewish, I was challenged by my fellow students at every turn.

Some white students looked at me as a novelty.

“Wait—you’re Jewish? How did you get Jewish?”

“I guess you could be Jewish, like Ethiopian.” My Jewish ancestry is Ashkenazi, actually, regardless of my skintone.

On the other hand, many black students bristled when I identified as mixed, saying I was black, because it was how I was seen. (Ascribed identity.) If I claimed I was “both,” then I was denying or diluting my allegiance to my father’s African heritage. I countered that I had to embrace all of my heritage, and not deny my mother’s background. I was informed that white people didn’t need or want me; blacks did. If I identified myself as Jewish—which, to me, had nothing to do with my race—students of color said I was identifying with the oppressor.

My Jewish ancestors, by the way, arrived by boat at the turn of the last century. Not one of them owned slaves.

So, eighteen years later, imagine my confusion at this curious phenomenon I’m finding on the internet lately. Dismissiveness, in some cases contempt, toward mixed-race people who identify as black. Now people have always taken issue with the words biracial people use to self-identify. For example, when Tiger Woods called himself “Cablinasian,” people became incensed; he was trying to deny his blackness. When Vin Diesel referred to himself as having “ambiguous ethnicity” while playing one Italian American character after another—people had a lot to say, much of it not for tender eyes.

But lately, as I browse the comments on articles that feature mixed race celebrities—writers, filmmakers, athletes, I’m seeing the pendulum swing a new way.

When President Obama calls himself black, many argue that he’s not black, he’s biracial and should stop “pretending.” They say the same about Halle Berry, who grew up being encouraged by her white mother to identify as black. Again, people take umbrage over Lacey Schwartz, producer and subject of the filmLittle White Lie, identifying as a black woman. After her film aired on PBS, the internet was abuzz with outrage over the fact that Schwartz, who is the child of a white, Jewish mother and black father, could not “accept herself as a biracial person.” The shocking part is that these comments came from mixed people, who know all too well how it feels to be dismissed by the generalizations of others.

How can one biracial person judge another for identifying “wrong?” And how is it suddenly not okay for people like me to call ourselves black? Sure, you can argue that, as the product of a white and a black parent, I’m only as black as I am white (regardless of my appearance). Since I cannot call myself white (see my profile photo? That would just be silly) I should not be allowed to call myself black. The reason that logic doesn’t work is my appearance.

I am not white. But I am Jewish, by way of my mother’s ethnicity. And in this way, I embrace and embody both sides of my heritage. (If my mother weren’t Jewish, but Irish or Italian, for example, I’d identify the same way, black and Irish or black and Italian. Jewish is an ethnicity as well as a religion.)

That’s why to be mixed is to be both-and, as well as sometimes neither-nor. Our identities are fluid by nature. No matter how white or how black we appear. So, instead of being canvasses for other people’s creative assumptions, let us be fountains of our own multiple heritage.

That’s why to be mixed is to be both-and, as well as sometimes neither-nor. Our identities are fluid by nature. No matter how white or how black we appear. So, instead of being canvasses for other people’s creative assumptions, let us be fountains of our own multiple heritage.

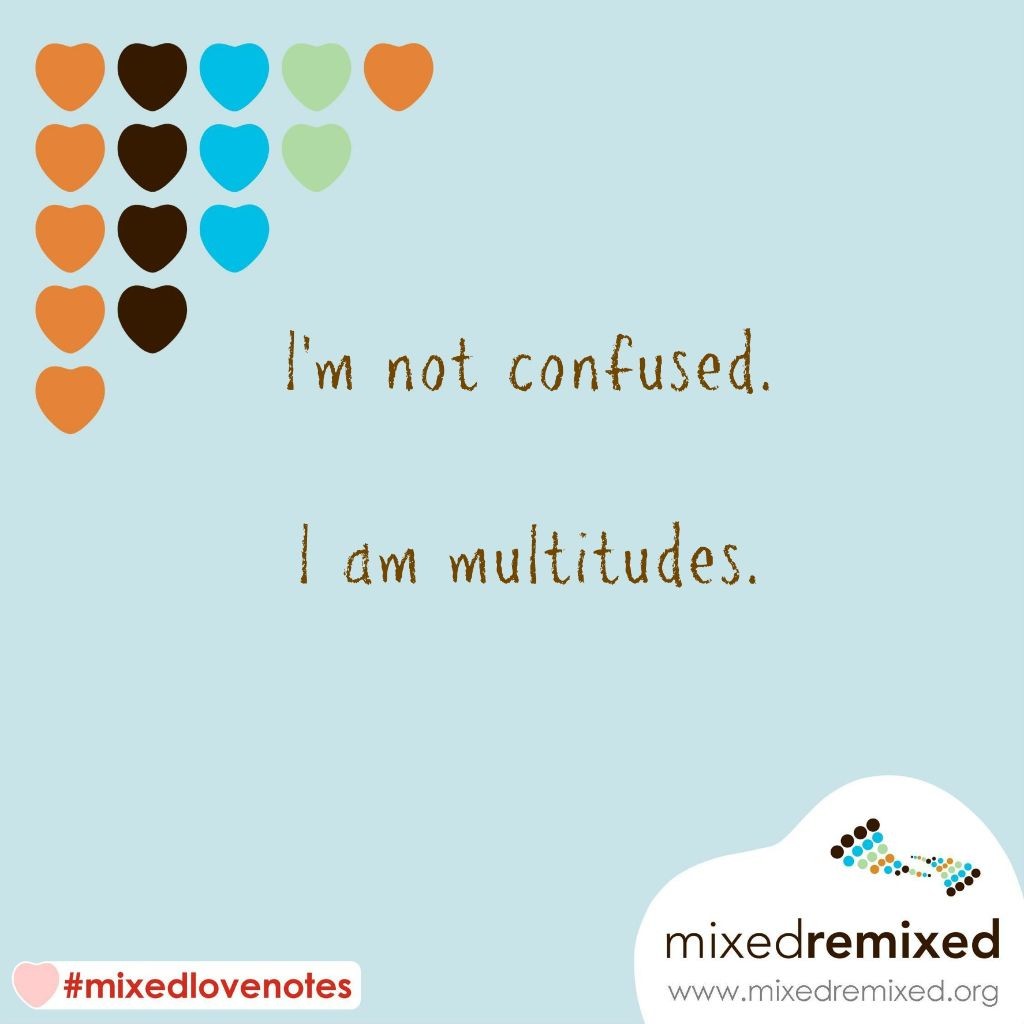

I have no claim to monopoly over the words I use to identify myself. All I ask is to self-identify, to claim all my heritage without challenge. We are all-inclusive, often in flux, sometimes leaning one way, sometimes the other. We’re not confused or out of touch with reality.

We’re not tragic either.-Lisa Rosenberg

[Tweet ” All I ask is to self-identify, to claim all my heritage ” #mixedrace #multiracial]