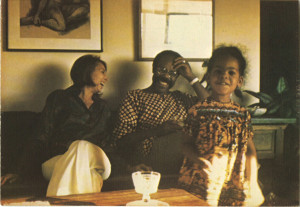

As a kid, I always got a big charge from being out and about with my parents. Sometimes people stared at us; sometimes they didn’t. In the 1970’s and 1980’s, when I was growing up in New York City, an interracial family wasn’t earth-shattering but it was still notable. I knew there were widely held stereotypes that families like ours fell apart. That interracial marriages bred confused, unhappy children.

People were curious. About me, the odd progeny, the spawn of two races. Was I confused? They wondered about my parents too. Did they really get along? Did they have anything in common?

I also knew that some people had opinions about my parents being together in the first place—a white woman and a black man—but we were a unit without a doubt.

There was strength in being us three. We laughed together, talked constantly, were the picture of a happy family.

That was what made me most proud, the reason the stares didn’t bother me. And there was something else that cheered me. When I was with both my parents, no one questioned that I belonged to them. As the common denominator of their wide-ranging physical traits, I made us look like we belonged together.

When I was alone with my mother, unless we were holding hands, it was a different story. I remember being very, very small, twirling around, close to my mother’s side, but not physically connected to her.

Someone demanded in a loud, irritated voice, “Whose child is that?”

I stopped twirling as my mother—indignant, nearly combative—stated, “She’s mine.”

That concept really hit home on a particular day when I was in kindergarten and my mother picked me up from school along with a playmate. My friend’s name was Lynn and her coloring was the same as my mother’s. Here is that memory.

*

My mother had her purse and some Zabar’s bags draped over one elbow, leaving only one hand free for my friend Lynn and me to share. We were crossing busy 79th Street, heading down Broadway to where Mom had parked the car. Between quick-stepping shoppers, Sabrett men pushing carts, and taxicabs swinging around the corner, not holding hands wasn’t an option.

Barely hip-level to passers-by, I remember nevertheless catching the eye of a woman a generation older than my mother. She smiled warmly, first at Lynn and then at my mother. Only I noticed the smile; they took it for granted. And, though I was just five, I guessed what the woman was thinking. She saw their matching, straight brown hair and narrow, angled noses. Lynn, to the eyes of the world, was my mother’s child. I, the brown girl with wild curls (my mother had no idea how to tame them), was just the friend, the outsider. In any case, I got no smile.

I let my gaze drop to the pavement: grey, rubbery, dank and moist. The rain had stopped an hour earlier, but the heaviness remained in the air. The sour smell of a wet, city spring rose to fill my nostrils. The soles of my navy blue Mary-Janes made a pleasing slap-slap-slapping sound on the sidewalk, spattering oily drops as I tread. Lynne’s Mary-Janes were pink.

Lisa W. Rosenberg – Festival Blogger

![TK-2012-05-19-002-007-Harajuku[1]](http://www.mixedremixed.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/TK-2012-05-19-002-007-Harajuku1-150x150.jpg)