Instead of a person of black and white parentage simply accepting the racial classification of black as their self-identification—and thereby shoving their white parent into the closet—mulatto identity is an attempt to move beyond black and white. —Mat Johnson

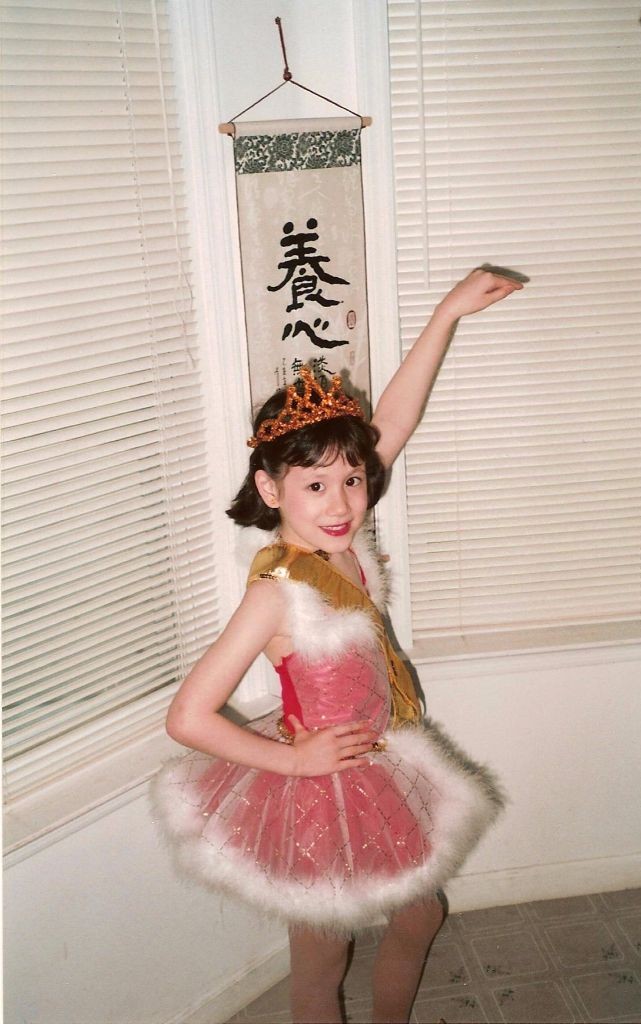

Being mixed often means arranging and rearranging the way you identify yourself. We perform different versions of ourselves based on time, place, and the audience at hand. During my childhood and adolescence, I moved from stage to stage dancing to others’ requests.

In useless efforts to “fit in” (into where, exactly, I never knew), I typically downplayed my Asian side. I avoided self-disclosure. When cornered, I said that my mom was from Taiwan. I tried to leave myself out of the discussion, and quickly followed up with something like, “But everyone says I look more like my [subtext: white] dad.”

When I began undergrad, I learned to regret my childish attempts to dissociate myself from my mom: from her (and my inherited) culture, languages, and story. I’d hurt my mom and restricted my intellectual and mental growth. So, in an attempt to connect with the side I’d been shirking, I did what many humans desperate for a quick fix do. I overcompensated.

As my brother (still) says, I became “obsessed” with my Asian-ness. I asked my mom to speak to me in Mandarin. I asked my dad to tell me how to spell this or that in pinyin. I wanted to know our Huang family history. When my mom called her mother, I wanted to speak to Amà and spout the little Mandarin I knew, in the poor excuse of an authentic accent I possessed.

I was Asian Asian Taiwanese Chinese. “Where’d you get that last name from?” Oh, I’d say, that’s just my dad’s. I take my shoes off when I’m indoors and wear slippers. Please take this fork and spoon away; I prefer chopsticks.

Hapa?

Asian Asian Taiwanese Chinese.

Per Mat Johnson’s Buzzfeed article, Why You Can Kiss My Mulatto Ass, I solely claimed the racial classification of Asian—thereby shoving my white parent in the closet. To my dad’s credit, he never complained or indicated that he felt neglected. He supported me. He shared the books he’d read during his undergrad years majoring in Asian Studies.

But, hapa.

I approach the stage. The curtain’s about to be drawn. It will rise, and I will turn to face the crowd. Dance, puppet, they’ll cry, dance. I take my place. I smooth my qipao, adjust my ornamental hairpin. But there’s something missing. Or I’m missing something. I hear a sound offstage. A rattling. A tapping.

The crowd’s murmuring peters out. They’ve dimmed the theatre lights.

I walk to the wings. I move toward the sound. A knocking. Quiet, but persistent. It’s coming from the supply closet. I reach out, and twist open the doorknob.

Bà? Dad?

He smiles. Nǚ ér. Daughter. I’m here to give you this.

I accept the offering and return to the stage. The intro notes play. I hear silence from the crowd.

The stagehands reveal my person. Cue the spotlight. My natural red highlights contrast with my dark dark hair. I lift my face to the audience, and flick my fan. They can read the Chinese characters and the translation. Complex. I am redoubled power. I am a tiger with wings. —Joy Stoffers, Festival Blogger