God Bless America

At a July 4th celebration this weekend, one of our friends brought a stunning cake iced with button-sized swirls of red, white and blue in the formation of an American flag the unboxing of which inspired the “oohs” and “aahs” I didn’t expect to hear until the fireworks later in the evening. No one wanted to cut the cake. It was as if we needed to acknowledge the revered symbol before enjoying the sugary treat beneath. Spontaneously, all assembled broke out a resounding version of “God Bless America.”

(In the pause between the end of the verse and the cutting of the cake I felt compelled to add: “A great song by Irving Berlin, one of America’s most renowned immigrants.” But I digress.)

Semiotics & Ideals

Semiotics is the fascinating study of symbols and how they become infused with meaning. The American flag, for example, has layers of meaning that go well beyond the forging of a 50-state nation from a recalcitrant 13 colonies. It stands for a spirit, a state of being, a set of values that have come be be associated with a vision we (or some) call the American Ideal.

Like action and money, symbols speak louder than words which is why the cutting of the American flag cake necessitated a spontaneous ritual. (Never, for example, have I witnessed a room break into “Let It Go” before devouring a delicately poised Queen Elsa alight a Frozen-themed birthday cake.)

The American Ideal is a bundle of values and social mores, the adoption of which will make America a better place for all fortunate enough to set foot on US soil. In theory, the ideal for which the American flag stands the promise of a Safe Place for everyone around the world.

As is the case with many symbols, the American flag is been imbued with an ideal that selectively omits unsavory historical fact, like America being born of violent revolution, becoming a global industrial superpower power as a direct result of its slave-build infrastructure, and growing to 50 states through the systematic genocide of indigenous Americans and war with the European nations who lay first claim to killing them first.

These conflicting interpretations of the American flag as a symbol and by extension of what it means to be American are boiling to the surfacing now in the form of a country that has not been as politically and ideologically divided since before the Civil War.

What, if any, are the implications of this new symbol of the Safe Place for those outside of Britain, specifically mixed race folk and under-represented minorities in the US? Can, or should the symbol be used outside of the culture and context in which it was conceived?

The Semiotics of the Safe Place

This is why we are witnessing the proliferation of new symbols and safe places both here and abroad: the rainbow flag, #BlackLivesMatter, the Asian American Arts Alliance, Mixed Remixed, and most recently, the safety pin.

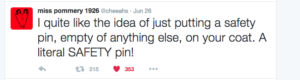

Yes, the safety pin, or #safetypin to translate it the format of a 21st Century symbol.

As quick YouTube search will confirm, following the Brexit vote race-related crimes in England have increased dramatically, by 57% according to the National Police Chiefs’ Council. In one such hate crime a Polish cultural center in the Hammersmith district of London that was vandalized on June 26—two days after the national declaration of the referendum result.

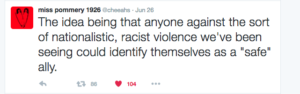

It just so happens that a writer who goes by the name Allison lives nearby. Later that day, Allison shared an idea she had via Twitter:

If press coverage is any indication of the importance of an idea, the fact that her story has been covered up by The Guardian, CNN and the BBC speaks volumes.

What, if any, are the implications of this new symbol of the Safe Place for those outside of Britain, specifically mixed race folk and under-represented minorities in the US?

Can, or should the symbol be used outside of the culture and context in which it was conceived?

Find out when we interview #safetypin author, Allison, in an upcoming post!

–Michael Maliner is a #hapa writer & festival blogger.