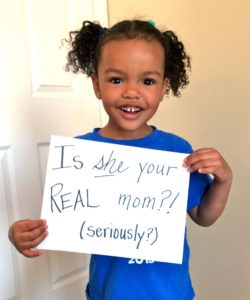

In the past three months, four different schoolmates have asked my biracial eight-year-old about the relationship between her mixed self and her white mom. The first occurrence was in January at the start of the day while hanging up backpacks, and a young lady asked M, “Are you adopted?” The second scenario took place in February during a school event at the skating rink, and a fellow second grader rolled up to M in the middle of the rink and blurted out, “Is that your real mom?” The third infraction occurred in March in a friend’s car on route to an after school activity, and M was again asked if she was adopted. Finally, the last inquisition took place on a playdate by an older sibling who also asked, “Are you adopted?” This almost teenager has been with our entire family one to two times per month for the whole school year! How could she have not figured it out on her own? Hmmm….something weird is going on here, and I am desperate to understand.

In the past three months, four different schoolmates have asked my biracial eight-year-old about the relationship between her mixed self and her white mom. The first occurrence was in January at the start of the day while hanging up backpacks, and a young lady asked M, “Are you adopted?” The second scenario took place in February during a school event at the skating rink, and a fellow second grader rolled up to M in the middle of the rink and blurted out, “Is that your real mom?” The third infraction occurred in March in a friend’s car on route to an after school activity, and M was again asked if she was adopted. Finally, the last inquisition took place on a playdate by an older sibling who also asked, “Are you adopted?” This almost teenager has been with our entire family one to two times per month for the whole school year! How could she have not figured it out on her own? Hmmm….something weird is going on here, and I am desperate to understand.

In light of these recent events, I have come to many conclusions. In this space, I will deal with one. Here we go.

In life we frequently encourage curiosity. Babies enthusiastically push aside hands to find that peek-a-boo face, which was previously covered up by a veil of fingers. Does your toddler want to know what ketchup and chocolate sauce taste like on a slice of multigrain raisin bread? Sure! Go ahead and try it. You only live once. Parents spend hard earned dollars on creepy crawly insects trapped in a jar so that they can show their children how caterpillars become butterflies. Do you want to know Ben Franklin’s middle name, how many spaghetti noodles could wrap around the earth, or the noise of an aardvark? Let’s google it.

In life we frequently encourage curiosity. Babies enthusiastically push aside hands to find that peek-a-boo face, which was previously covered up by a veil of fingers. Does your toddler want to know what ketchup and chocolate sauce taste like on a slice of multigrain raisin bread? Sure! Go ahead and try it. You only live once. Parents spend hard earned dollars on creepy crawly insects trapped in a jar so that they can show their children how caterpillars become butterflies. Do you want to know Ben Franklin’s middle name, how many spaghetti noodles could wrap around the earth, or the noise of an aardvark? Let’s google it.

However, should there be a limit to curiosity? Do we sometimes need to keep our curiosity in check? Have we taught our children the boundaries of curiosity? Here’s a fun fact that may not be on the top ten list of golden nuggets to pass down to one’s off-spring (but perhaps it should):

In the words of Laura Horwitz of We Stories (a St. Louis not-for-profit organization designed to raise diversity awareness among white families through children’s literature), “examining our own curiosity, managing it, and sitting with not knowing are big parts of becoming more thoughtful about whiteness. All families in all forms are beautiful and have lots of stories! I don’t need access to every family’s story (nor would I expect to offer mine) at a whim.”

Children need to know that sometimes it is not okay to ask. Sometimes you do not get to satisfy your curiosity.

Since age 3, I have taught my children to stay quiet when they notice a person who does not fit their tiny little definitions of “normal.” They can either wait until later to discuss what they saw or whisper in my ear if they just can’t restrain themselves. As a result of this rule, I have received whispers about pink and green hair, different body shapes, tattoos, piercings, wheel chairs, service dogs, missing limbs, birthmarks, vitiligo, accents, and the list could go on. Their observations frequently lead to wonderful dialogues about the beauty of differences, and sometimes our talks end in unanswered questions. For example, I don’t know why your friend has a misshaped ear, and we will never get to know unless that person decides to tell you.

My biracial family may be the subject of some other child’s whispering. I can imagine a hushed voice in the grocery store, “Mommy, why is that little girl black and her mommy is white?” That’s totally cool. I hope that whispering leads to an eye-opening discussion. I just wish that some people could teach their eight-year-olds the rule that my four-year-old already knows:

My biracial family may be the subject of some other child’s whispering. I can imagine a hushed voice in the grocery store, “Mommy, why is that little girl black and her mommy is white?” That’s totally cool. I hope that whispering leads to an eye-opening discussion. I just wish that some people could teach their eight-year-olds the rule that my four-year-old already knows:

Contain your curiosity. Just because you want to know, does not always mean you get to know.

by Amy Hayibor, Festival Blogger, Mother in the Mix

Follow Amy on Twitter: www.twitter.com/motherinthemix

Follow Amy on Facebook: facebook.com/motherinthemix/

I grew up in a biracial household, my mother Asian and my father white. I also have created a biracial household of my own, but in a slightly different way: my son is biological and my daughter is adopted from Asia.

(Does that make us a biracial family? I honestly don’t know. But coming to an understanding about our place in society necessitates pushing boundaries.)

We get all sorts of questions, especially when my Asian daughter spends time with her Asian grandmother. I agree, children must be taught the importance of a whispered query in a parent’s ear followed by a private conversation.

I am a woman of mixed descent, black, white and Jewish. On one hand, I completely understand that people need to know when to respect another’s humanity, and keep their mouths shut. On the other hand, I believe if people don’t discuss multiraciality, there will be a lack of understanding. Could it be that there needs to be a forum for discussion, rather than no discussion at all? What are you trying to accomplish by children not asking?

Hi! Thanks so much for reading my article. I always welcome discussion. As a parent, I feel like I have done my job by educating my kids on the “uniqueness” of our family. We have talked about skin color since my kids were able to talk. We have thoroughly discussed every single topic that a person could think to discuss with his/her mixed child. We are an exceedingly open family. I have prepped my kids for scrutiny, questions, and life in that department.

However, I have also done my job as a parent on educating my children about disabilities (physical, learning, mental, behavioral), adoption, foster care, world religions, atheism & agnosticism, divorce & remarriage, heart aches for military families, homosexuality, and many more. With the exception of divorce, not a single one of these topics affects ANY person in our immediate circle of friends and family. However, I educate my kids because I want them to be kind and aware citizens. Furthermore, I educate them at the right time – not in the middle of the grocery store after my kid blurts out “Why is that guy in a wheel chair??!!!” I have taught my children to come home and ask and discuss – not confront the person and potentially make that person feel out of place or different.

I simply wish that other parents would do their job – Educate their kids and teach their kids to come home and ask.