It’s 2016: social media, globalization, and exoticism are “in.” Come not as you are, but as you wish you could be. At least, that’s the impression I’m gathering.

As a mixed-race child, I knew that some people—like my Caucasian father—found Asian culture interesting. Sometimes I found these interests described as “fascination,” which made me uncomfortable. But since I had yet to learn the noun phrase “cultural appropriation,” I ignored any feelings of discomfort.

When I became a sophomore at Rutgers University, I took a course titled “Asian American Literatures in English.” And during each class, my professor cleared a section of my mind mirror. I reflected on my experiences. I recalled the feelings of discomfort.

To appropriate, according to the third definition in the Oxford English Dictionary (can you tell I was an English major?), means “to take possession of for one’s own, to take to oneself.” For those of you who avoid British dictionaries, the New Oxford American Dictionary defines the verb “appropriate” as to “take (something) for one’s own use, typically without the owner’s permission.”

My discomfort was tied to the power dynamics inherent in cultural appropriation. One party—the majority—absorbs aspects/an aspect of a minority’s culture. In the process of absorbing/commandeering, the minority becomes disenfranchised.

If you’ve read this far and you’re my aerospace-engineer brother, you’re figuratively glaring at me. For the benefit of him and other like-minded people, I shall chuck my academic hat. Simply put, being stolen from pisses us off. And we’re doubly PO’ed when you’re twice our size and have been lording over us since we wailed for the first time.

Yes, part of the problem with appropriation is lack of permission. But also, the majority usually takes your holiday/costume/food/ritual/ceremony without consulting you for accuracy. How’s that extra burn feel?

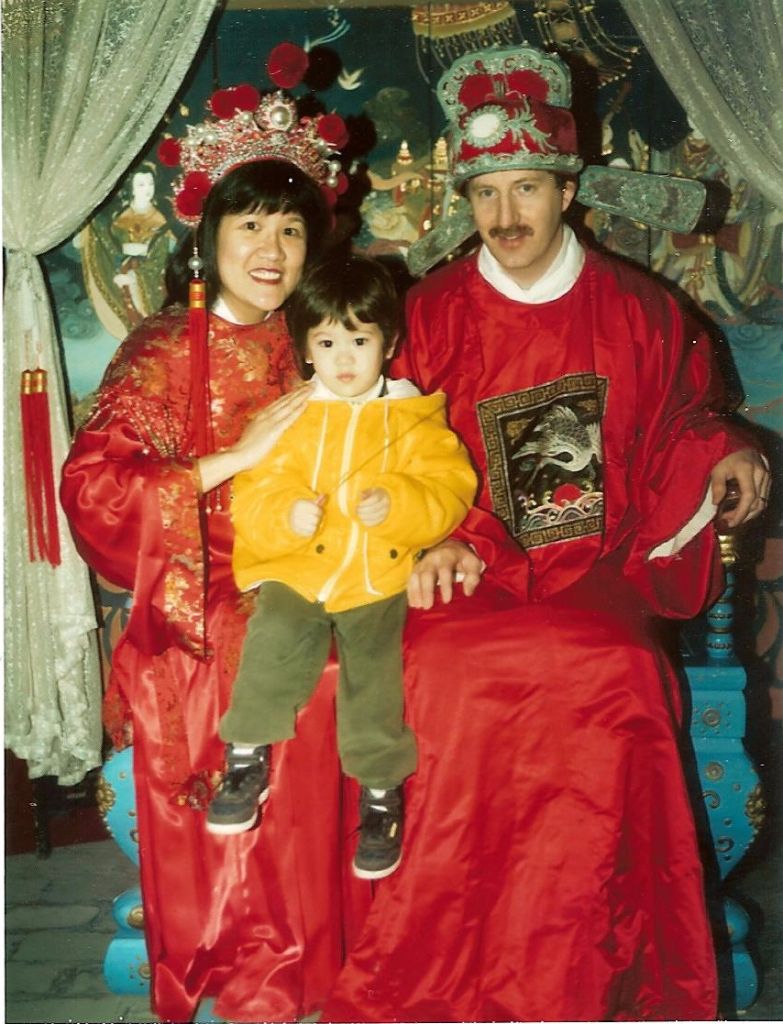

Back to the personal. I always thought my dad appreciated my mom’s culture. That he knew he was a White Straight Man (WSM), and that he respected her and valued her heritage. Sometimes my parents would dress up in traditional yīfu [clothing], but Mom selected clothing for Dad. When Dad and I went to the Hong Kong Supermarket or H Mart, he spoke Mandarin with the check-out ladies to put them at ease, not to show off. Dad asked me questions about my experiences; he never assumed to know them.

There have been (angst-ridden) times where I’ve accused Dad of culturally assuming. Nonetheless, because of his cultural awareness—and where he, Mr. WSM stood in the global picture—I never sensed appropriation.

Now that I’m in my mid-twenties, I know what makes me feel uncomfortable. Yellow fever (and I’m not referring to the tropical viral disease transmitted by mosquitoes). Masquerading as a [insert minority group here] person without below-the-surface knowledge. Obsession with “the other.” Taking instead of participating.

Yet I also know that all these lines intersect. When I wear a qipao, am I fifty-percent appropriating? What rights do I have to dance hip-hop? To speak the Spanish I studied for nine years?

I don’t know. But I ask. I think. And, most importantly, I listen. —Joy Stoffers, Festival Blogger