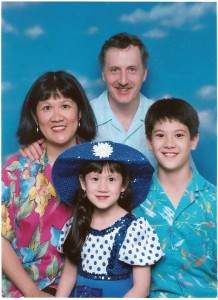

To the right is a picture of my family, taken in the early ’90s. During the heyday of America Online—the dial-up version. The ’90s, long befo re We Are the 15 Percent, Mixed Families on Tumblr, Stunning Portraits of Mixed-Race Families, and Mixed Race Babies on Facebook. Before you could Google anything, let alone “mixed-race family/baby/women pictures.”

re We Are the 15 Percent, Mixed Families on Tumblr, Stunning Portraits of Mixed-Race Families, and Mixed Race Babies on Facebook. Before you could Google anything, let alone “mixed-race family/baby/women pictures.”

Children tend to love posing for photos. Childhood is often the period of time you experience before gaining self-awareness. “I feel self-conscious” usually isn’t part of a child’s thought process. But then we grow up. We realize that people look at us with the same scrutiny we use to look at them.

We become entirely self-conscious.

This self-consciousness develops in different forms for different people. Some hide from the camera while others run toward it. Still others are ambivalent or apathetic. The majority, however, seem to either hate or love photographic documentation.

Then came the advent of the internet (as we know it today) and social media. Then came selfie nation. We became inundated with images. With advertising. With self-advertising.

The virtual world exploded with images of mixed and biracial people—with and without the context of family. People took pictures of themselves, of others, and posted them as models (or not) of multiracial success (i.e., beauty).

Of course, changes in racial demographics are likely tied to this photographic phenomenon. (I won’t make any data-based claims, but I imagine tracing U.S. Census data and the virtual release of multiracial images would make for an interesting doctoral dissertation.)

Many a Facebook page/group, website, or Tumblr was created to share photos of multiracial people. Whole forums (I refuse to link to these) popped up devoted to celebrating or disparaging the people represented by these images. For public consumption and exchange, there exist mixed-race images of celebrities; babies; families; men; and women and girls—the last of which are often conflated.

Yes, celebrating representations of ourselves is self-esteem boosting and generally positive. (You know what’s coming next, don’t you?)

But.

There is a fine line between celebration and fetishization. Between celebrating and essentializing. The problem with defining people by images lies in the definition of image.

À la OED, an image, noun, is “An artificial imitation or representation of something, esp. of a person.” Note the key words “artificial imitation” (I know, rather redundant, but this isn’t a grammar post) and “representation.” Moreover, an image is a particular interpretation of a person, grounded in time, space, and camera angle.

Take, for instance, the Facebook community Mixed race girls. If you scroll through the pictures, as fellow blogger Terri pointed out, the women (because they appear to be adults, not children or adolescents) seem to look the same. The images are arguably sexualized. It gets better (read: worse). Here’s what the community’s “About” section states: “Mixed race girls can be known as, Mulatto, Biracial, Mixed race, they look like light-skinned black girls, but enjoy the page, pictures and videos.”

It’s not my place to judge the images, the women they represent, or the community founders. But I will make an argument.

The problem with images is that we tend to forget that they stand for more. They are placeholders for people. For flesh and blood and feelings and tears and stories. We cannot be reduced to images, no matter how great the camera taking them or the resolution of them, no matter the DPI.

An image is a snapshot of us. A glimpse into the window that is our outward appearance. Let’s try to remember this. We can and should celebrate our likenesses. But we should remember that an image is simply one time-bound component of our ever-shifting, full selves. —Joy Stoffers, Festival Blogger